Bookbinding

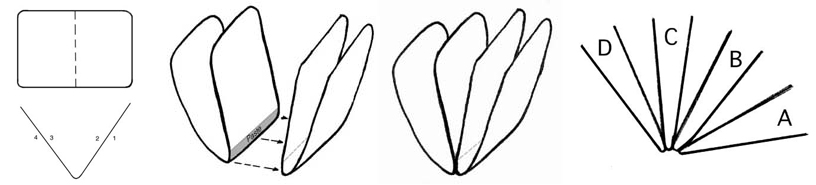

Diagrams by Li Yi and Colin Chinnery

DOWNLOAD THIS PAPER (PDF 2.1MB)

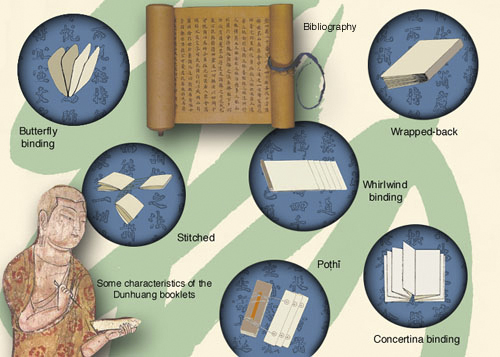

The history of Chinese bookbinding has always suffered owing to a lack of material evidence. The various book formats discovered among the Dunhuang document collection provide a wealth of information previously out of reach to scholars. However, this resource has remained relatively untapped, attention instead being focused on the textual content of the documents. Bookbinding is just one of many aspects to the study of the Dunhuang collection as physical artefacts. This site, by combining textual descriptions with diagrams illustrating binding techniques and photographs of the actual objects, aims to give a comprehensive introduction to the different kinds of Chinese bookbinding contained in the Dunhuang collection of the British Library.

Some characteristics of the Dunhuang booklets

In AD 755 a major rebellion in China forced the government to recall its troops from the western regions. The armies of the Tibetan empire moved in to fill the vacuum and most of the Silk Road towns, including Dunhuang, were under Tibetan control for the next century. Trade with central China was cut off and therefore previously imported items, such as high quality paper, were no longer available. Although Dunhuang was retaken by local troops loyal to China in AD 851, by this time Chinese imperial power was in decline and the contacts of the western regions with the centre were still not strong. From the quality of the paper and the colophons to some of the texts, we know that many of the booklets found at Dunhuang date from the late-Tang and Five Dynasties period (AD 907-960). Unlike many other items in the Dunhuang collection, the majority of these booklets were not produced in central China and brought in to the region, but were made locally in Dunhuang, often by the very people who used them.

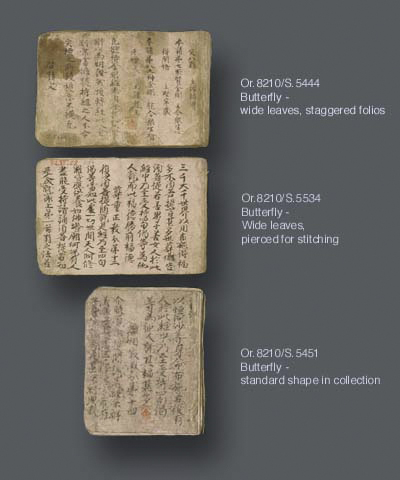

One of the most interesting aspects of the Dunhuang booklets is the sheer variety of different formats. Not only are there examples of both butterfly binding and thread binding, but there are also many booklets which have been made by combining features of different formats to create a new type of binding:

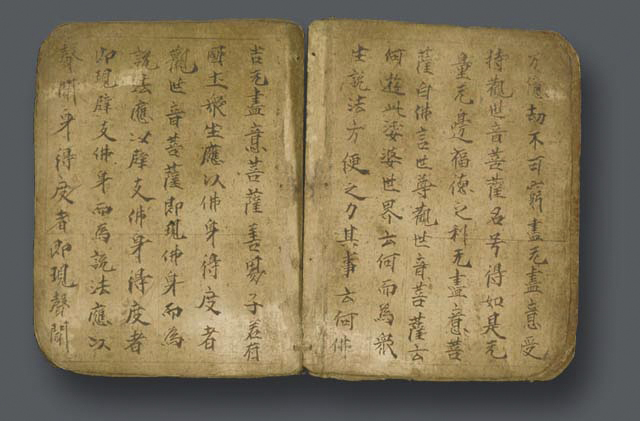

Stitched binding, butterfly binding

and 'wrapped back'

This book has been bound in the butterfly style. The folded leaves were then stitched together at the top and bottom, and two layers of paper were pasted to the back of the book for protection. In the Dunhuang collection there are booklets in all different combinations of these three forms of binding: Stitched and butterfly binding; butterfly and 'wrapped-back'; stitched binding with 'wrapped-back'.

Or.8210/S.5556

Dimensions (cm): 12 x 15 per page.

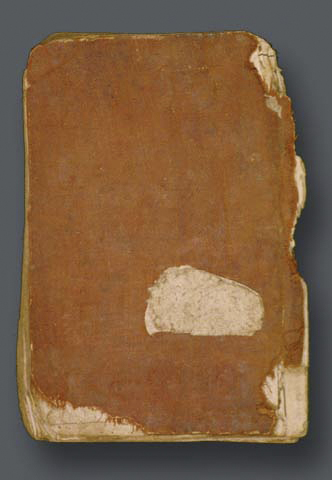

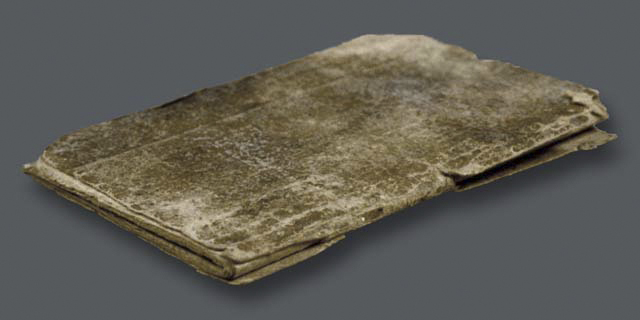

Cloth backed book

This butterfly bound book has had a layer of red cloth pasted to the outer cover. This is the only such example in the Dunhuang collection of the British Library.

Or.8210/S.5535

Dimensions (cm): 11 x 17.3

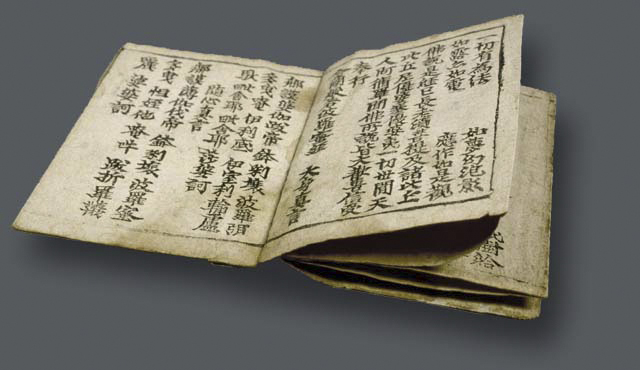

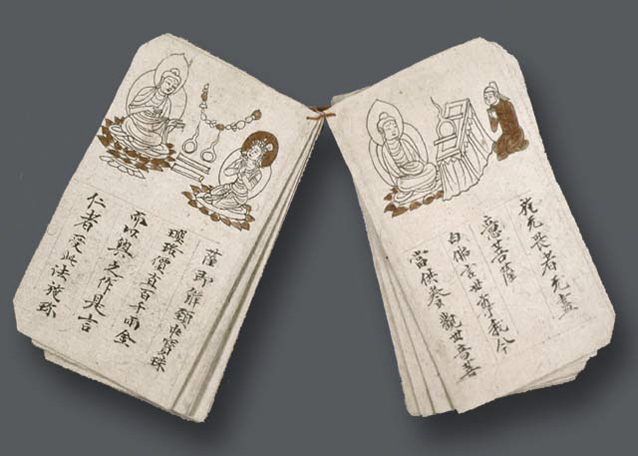

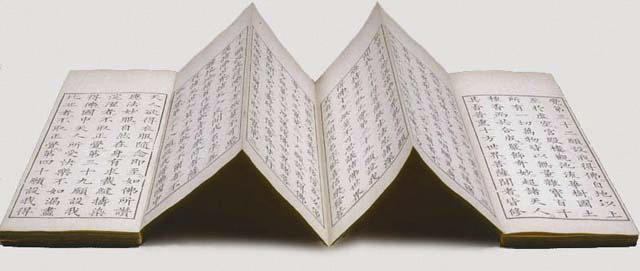

Concertina pasted in the butterfly style

This item is a mixture of the concertina and butterfly formats. It is also the only printed booklet in the collection. Originally folded in the concertina style, the folded edges of the book were pasted together like the folded leaves of the butterfly format. This simple modification to the concertina format would have made the book easier to carry and to turn the pages.

Or.8210/P.11

Dimensions (cm): 10 x 14

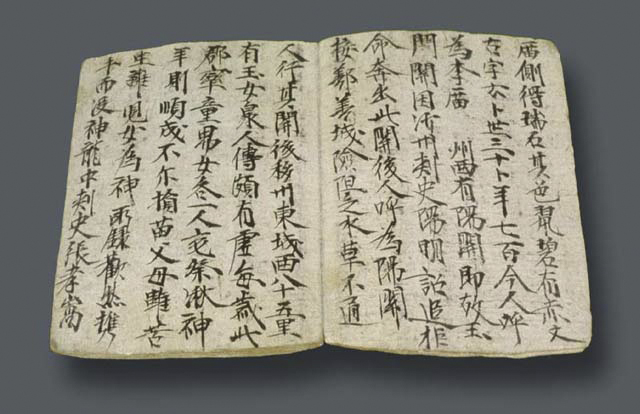

Stitched gatherings in elongated concertina or pothi shape

This stitched booklet has the dimensions of concertina or Chinese pothi formats.

Or.8210/S.5475

Dimensions (cm): 10.5 x 27

Pothi in the shape of a butterfly book

Although the shape of this book suggests the butterfly format its pages have not been pasted together. Instead, holes have been pierced through the middle for it to be strung together in the pothi style. There is little indication of wear around the edges of the holes, therefore it is unlikely that string was ever used.

Or.8210/S.5668

Dimensions (cm): 16.7 x 13

Although many different methods of bookbinding are represented in this collection, no direct connection with the bookbinding developments of central China can be proven. Moreover, unless it can be shown that a particular bookbinding style found in this one region was practised on a larger scale, it can only be assumed that these different formats were created by individuals according to their own ideas. This is perfectly demonstrated by three booklets in the Dunhuang collection that were all copied and bound by a man in his eighties, each by a slightly different method.

In a region where resources were scarce, every effort must have been made to ensure books lasted as long as possible. Moreover, most of these booklets were made to be portable and consulted frequently, and therefore they would have been subjected to further strain. This would have been another factor to consider when the booklet was made. The earliest form of folded-leaf book, the butterfly book, tended to come apart easily, and it is natural that people would have thought of ways to remedy this weakness. Whether stitching or backing techniques were developed as a result of experimentation, or through some influence from outside, is not yet known. However, improvisation in bookbinding can be clearly seen in several examples of the Dunhuang collection where modifications have been applied to a book that were obviously not originally intended.

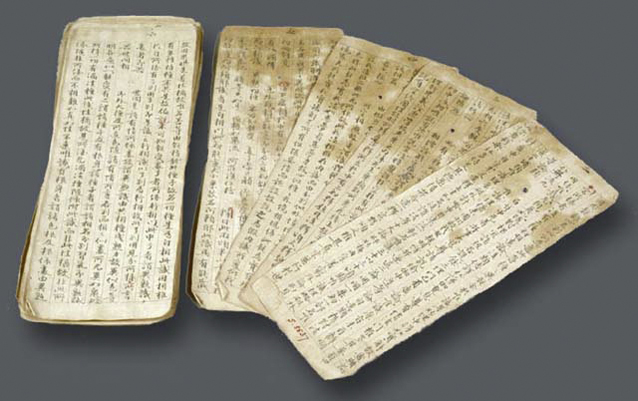

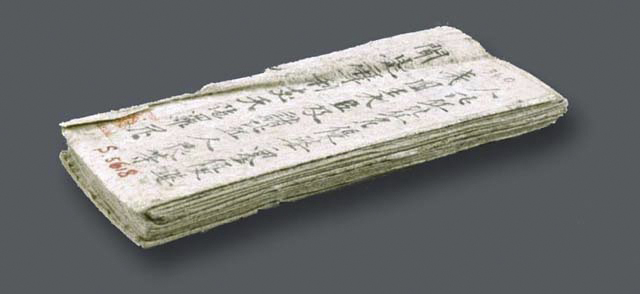

This booklet has been folded in half due to the length of its pages. After being folded it has similar dimensions as the majority of other booklets in the Dunhuang collection.

Or.8210/S.5433

Right: The stitching of this booklet was apparently not anticipated since the thread passes straight through the characters near the centre of the page, forcing them into the fold. This booklet, and a number of others like it, have been stitched together like pieces of cloth.

Or.8210/S.5678

There are also many examples of booklets that have been deliberately bound in a way which combines two or more techniques, indicating that the local bookbinding process also evolved.

There are some rare examples of such combined bookbinding that were probably produced in central China and taken to Dunhuang. The two examples Or.8210/S.5668 and Or.8210/S.5603 quite clearly show that the pothi style holes were a deliberate feature of two very different forms of book: One in the shape of a butterfly bound book, and the other a concertina. What these booklets demonstrate is that there was a certain influence between different styles during the same period in central China as well as in Dunhuang.

It is very unlikely that the bookbinding experimentation that took place in Dunhuang did not also take place elsewhere in China. A Song dynasty scholar of central China recounts that he was so fed up with his butterfly book coming apart that he had it stitched. However there are no extant physical objects from central China to support or clarify brief textual references such as this one. The Dunhuang booklets are special because they represent a process that must have also existed in central China, a process that made the evolutionary link between subsequent book formats.

Butterfly binding (hudie zhuang)

Butterfly binding played a pivotal role in the history of Chinese bookbinding. The popularity of this form of book in the Song dynasty (AD 960-1279) marked the end of the scroll and the beginning of the folded leaf book.

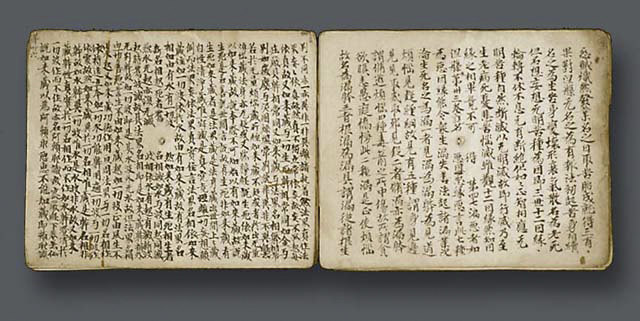

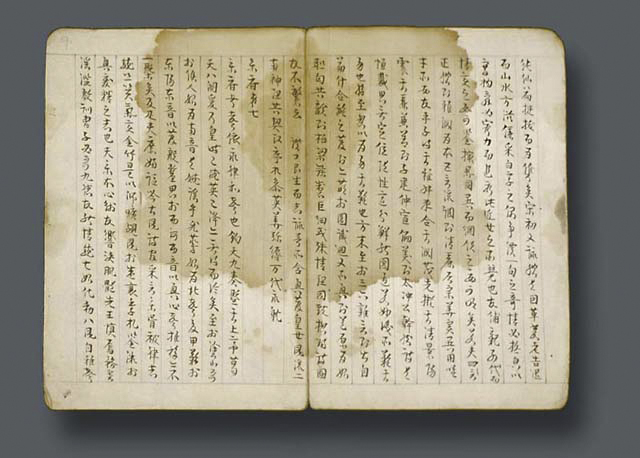

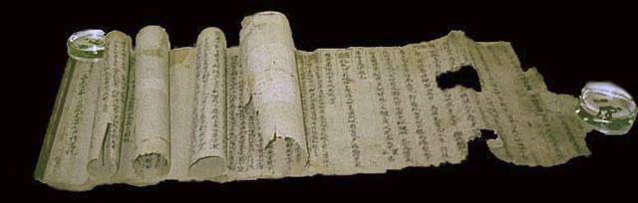

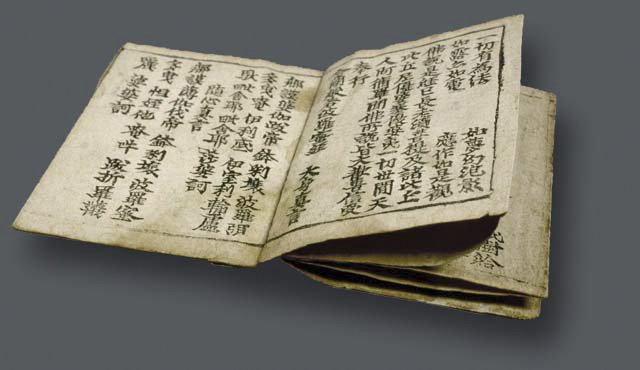

A copy of the Wen xin diao long, a discussion of various kinds of literature.

Compared with other booklets in the Dunhuang collection the paper of this manuscript is exceptionally smooth and fine, and the handwriting refined.

Moreover, this is not a religious text, unlike the majority of booklets made in Dunhuang.

Therefore, it is very likely that this booklet was made in central China.

Or.8210/S.5478

Dimensions (cm): 11.7 x 16.8 per page

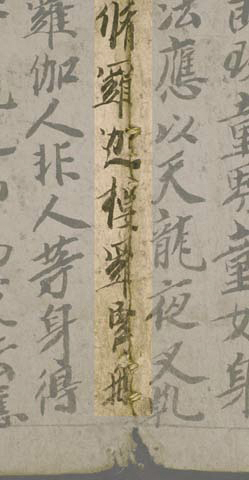

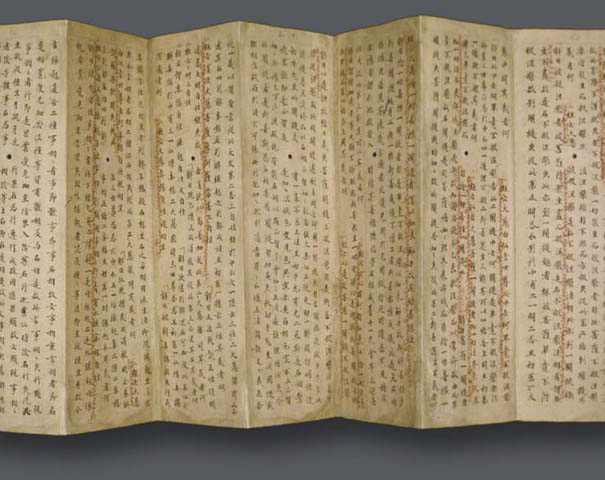

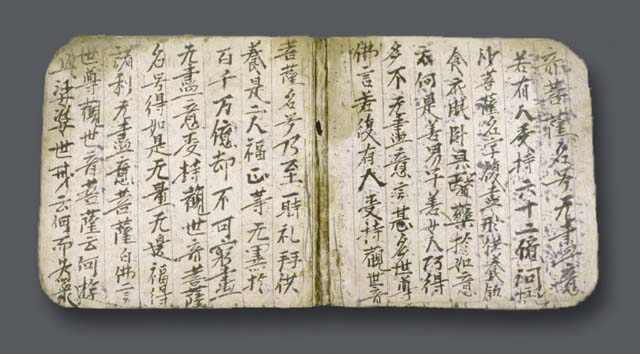

The recto of a folded leaf. The colophon of this manuscript indicates that it was copied in AD 906 by an 'old man of 83'.

Or.8210/S.5451

Dimensions (cm): 11.5 x 14.3 per page

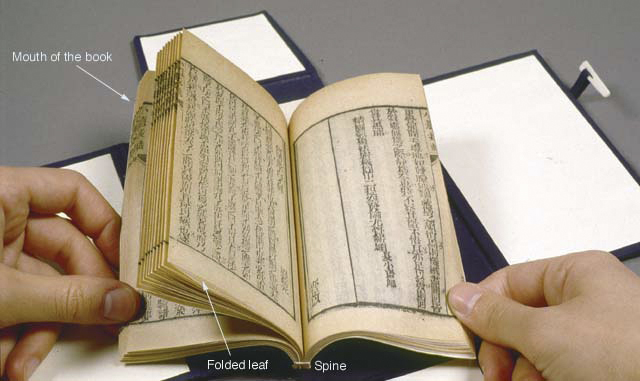

This photograph shows the way in which the folded leaves are pasted together. Facing this direction is the recto of a folded leaf.

Or.8210/S.5451

Indeed, butterfly binding was the first Chinese book format to depart completely from the concept of the scroll. Although both concertina and whirlwind bound books had characteristics of the leaf book, they were both strongly influenced by the scroll and still shared many of the its features. Butterfly binding, on the other hand, managed to break away from this bookbinding tradition, starting on a new direction for the making of Chinese books.

The collection of booklets in the Dunhuang collection of the British Library has several examples of butterfly binding. Some of these booklets date to the Tang dynasty (AD 618-907), and unlike many of the scrolls in the Dunhuang collection, these booklets were mostly locally produced.

Since Dunhuang was such a distant outpost of the Chinese empire, it is very likely that the format had already existed for some time in central China. The existence of these booklets, therefore, suggests that butterfly binding existed at an earlier time than was previously thought. It is very difficult to know exactly how this format evolved. Perhaps the most important innovation of this format was the development of the folded leaf. A butterfly bound book was made by folding sheets of paper in half, forming four sides each. Paste would then be applied to the folded edge of the paper, and the folded sheets would be stacked together so that the folded edges met to form the spine of the book. The shape of the leaves and the manner in which the book opened and closed resembled the wings of a butterfly, therefore the book was given this rather descriptive name.

This simple and compact design meant that the book could hold far more text than any other format. Moreover, it was much easier to carry around than either the scroll, which was an awkward shape, or the concertina, which did not hold together well. This was especially important for Buddhists who liked to keep sutras on their persons to recite as they moved from place to place. Also in contrast with other types of book, the butterfly format did not have a strong connection with the text it contained. Concertina and Chinese pothi formats were predominantly used by Buddhists, and whirlwind books seemed to relate mostly to reference works. Butterfly books were not restricted to any particular group of users. This meant, in effect, that it was the first book format that could replace the scroll.

By the time butterfly binding appeared, the art of wood block printing had already reached maturity. A copy of The Diamond Sutra in the British Library (Or.8210/P.2) printed in the year AD 868, is a perfect example of the refinement block printing techniques had achieved by the ninth century. Although the earliest printed books in China were produced in the scroll format, by the Song dynasty, most books were produced in the butterfly format. Owing to the nature of the printing block, individual leaves were much more suited to printing than the continuous roll of paper of the scroll. Moreover, since the individual leaves of the butterfly format were folded in half, it meant that two consecutive pages could be printed from one block.

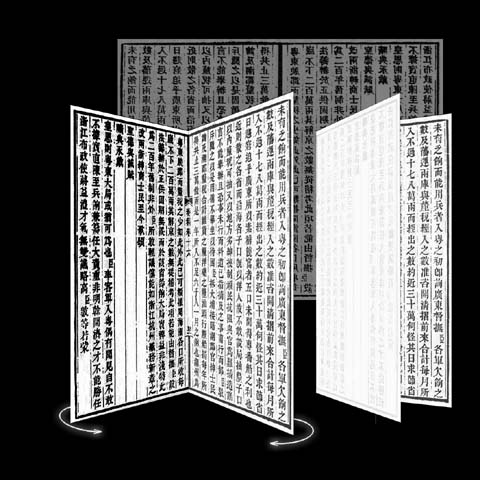

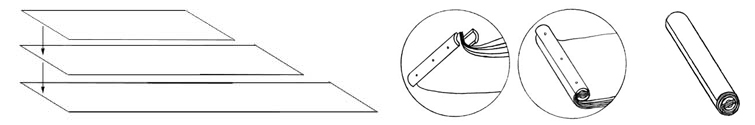

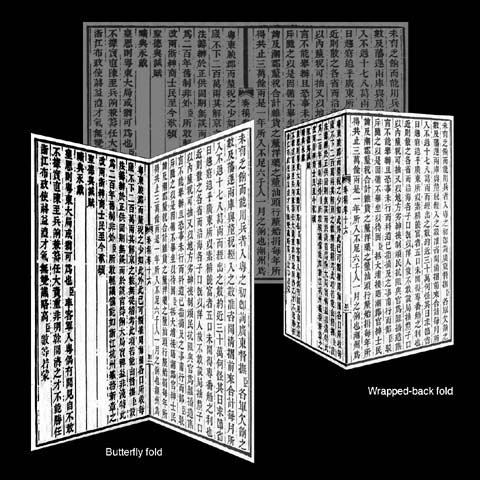

This shows a folded leaf printed with one wood block (in the background) to form a double page. The arrows indicate the direction of the fold in butterfly binding. Each folded page is only printed on one side, the other side remains blank.

The reverse side of each folded leaf is left blank.

This concept was a very important development of the printing block, and it stayed at the heart of Chinese printing until the reintroduction of movable type by the West in the nineteenth century. Therefore, this special relationship butterfly binding had with the printing block helped to make this format survive and eventually develop into other forms of binding.

Ironically, the relationship with the printing block was also the greatest weakness of butterfly binding. Since the printing block printed two consecutive pages, only one side of each leaf could be printed on. This meant that every second page of the book would be blank.

This was obviously a major problem that had to be resolved, so the structure of the folded leaf was changed. The result of this change of design was called wrapped-back binding. This format effectively replaced butterfly binding during the Ming dynasty.

Despite this strong connection with printing, there are no examples of printed butterfly books in the Dunhuang collection. This is mainly due to the relative isolation of Dunhuang during the late Tang and Five Dynasties which not only meant that much fewer books were brought into Dunhuang from central China, but also meant that printing technology was slower to reach the region as well.

Due to the popularity of this format, there are more examples of butterfly binding than any other form of booklet in the Dunhuang collection. These include many 'hybrid' books (see Characteristics of the Dunhuang Booklets) which mixed different formats together that apparently existed at the same time in the Dunhuang region.

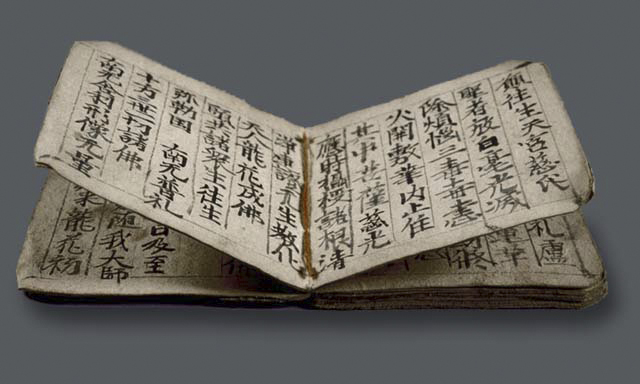

Stitched binding (xian zhuang)

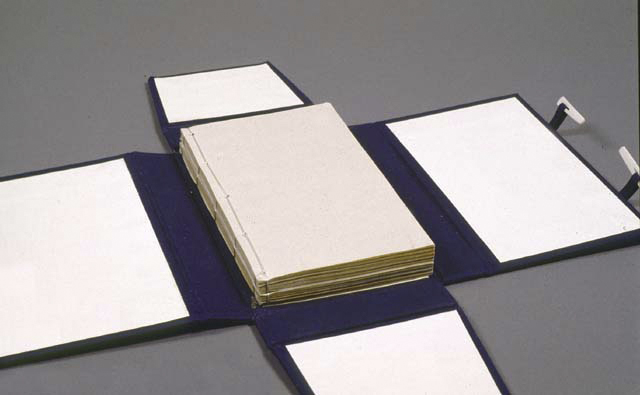

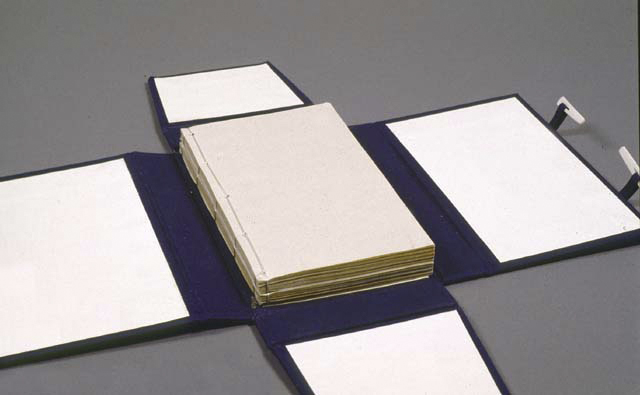

Typical thread bound books with covering case.

The stitched booklets in the Dunhuang collection can help us to understand more about the history of Chinese bookbinding.

Thread binding became the predominant Chinese book format late in the Ming dynasty (AD 1368-1644), and represents the last phase in the history of traditional Chinese bookbinding. The vast majority of books handed down to us from China's imperial past are in this format, therefore many will be familiar with it.

Although the popular thread binding of the Ming and Qing (AD 1644-1911) dynasties was invented relatively recently, the history of its development goes back much further in time.

There are a number of booklets in the Dunhuang collection that have been bound with thread. The most striking aspect of these books is the fact that they appeared at such an early period. The colophons on some of the booklets tell us that they were copied and bound during the Tang dynasty (AD 618-907), some six hundred years before the emergence of mature thread binding books in the Ming. What is also surprising is that there was a whole variety of stitching techniques already being applied. It would be interesting, therefore, to have a look at some of these different techniques in order to understand the nature of this development in bookbinding.

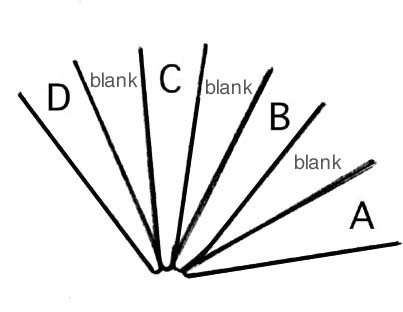

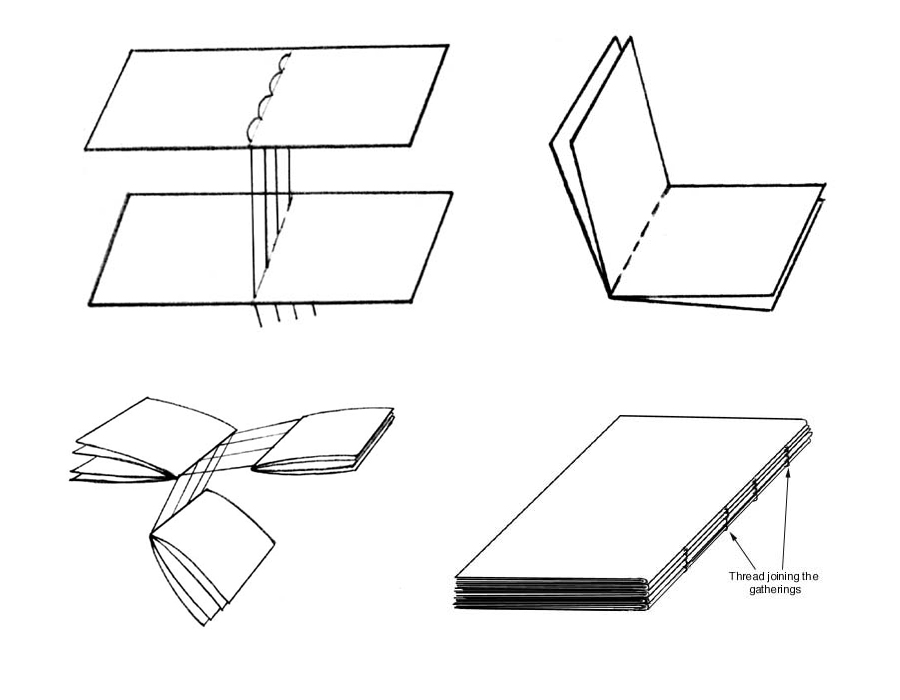

Stitched gatherings

Each gathering consists of two or more sheets of paper which are joined together with thread at the fold (see next diagram).

The spines of each of the gatherings are sewn together.

All the spines of the gatherings are brought together to form the spine of the book.

Stitched gatherings

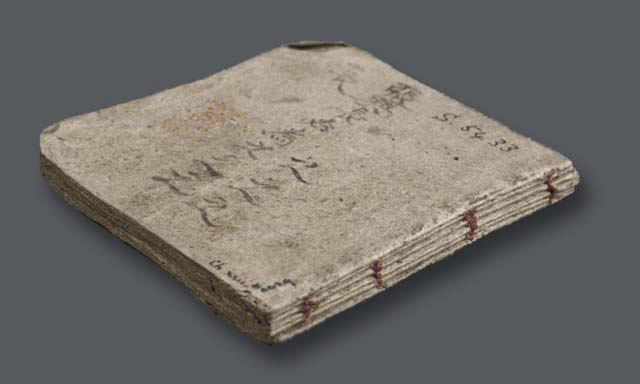

The centre of this booklet reveals the stitching that binds the gatherings together.

Or.8210/S.5433

Dimensions (cm): 8.2 x 9

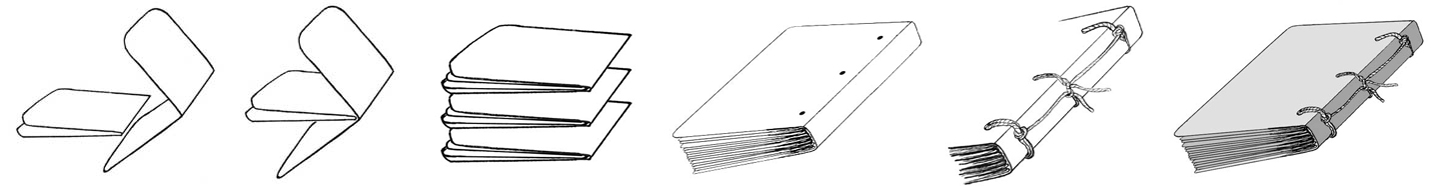

Stab stitching

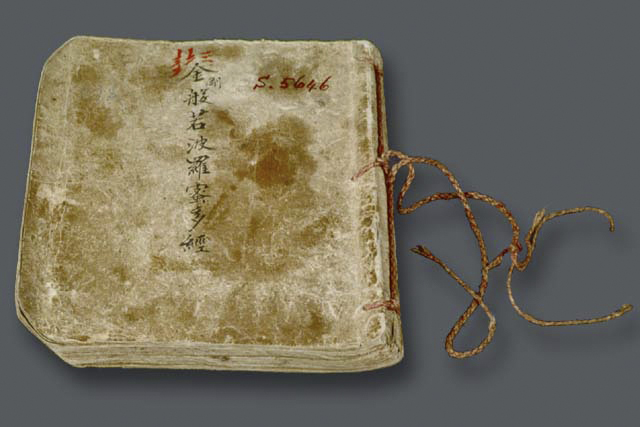

Diagram representation of the binding of Or.8210/S.5646

(1) The pages are folded and brought together into gatherings.

(2) The unstitched gatherings were then piled together.

(3) A cover was placed around the back of the book, then three holes were pierced through the book near the spine.

(4) Two strings were used to pass through the three holes and bind the book at the spine.

Or.8210/S.5646

Dimensions (cm): 12 x 10.5

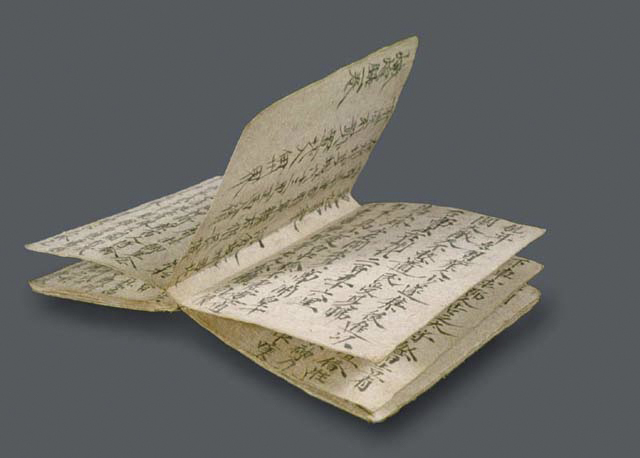

Stringing together

This book has the simplest thread binding method of all the documents in the Dunhuang collection. The folded leaves are gathered together without being pasted and simply strung together with a short length of thread at one corner of the spine.

Or.8210/S.6983

Dimensions (cm): 10 x 17.7

Most of these stitched booklets in the Dunhuang collection were bound into gatherings. This was a very new method of putting a book together for the Chinese. There seems to be no form of book that either led up to that technique or developed from it afterwards. This makes it unique in the history of Chinese bookbinding, and it certainly deserves more investigation. Although it is not known exactly how the stitched gathering book developed in China, it is possible to imagine why this kind of book did not last.

Although printing was developed during the Tang dynasty, it only became popular during the Five Dynasties (AD 907-960) and the Song dynasty (AD 960-1279). Owing to the nature of the printing block, which was designed to print two consecutive pages, butterfly binding became the predominant binding format until the wrapped-back book took its place. The development of wrapped-back binding was also related to printing and the nature of the printing block (see article). The stitched gathering format, however, differed considerably regarding its relationship with the printing block. Because of the way the pages were folded it is impossible to print two consecutive pages on this form of book. Therefore, it is possible that this incompatibility with printing techniques precluded the survival of the format.

The remainder of the booklets in this collection seem to have been stitched in the butterfly style. This development is much easier to understand than the stitched gatherings. The butterfly format was the most popular method of binding leafed books until at least the end of the Song dynasty. However, a weakness of butterfly books is that they came apart easily, therefore, stitching could have been applied in order to reinforce or repair a book. The scholar Wang Zhu of the Northern Song dynasty (AD 960-1127) wrote that he had exactly this problem with butterfly books, and stated that had them stitched to make them more durable.

This very simple explanation of the appearance of stitch binding during the Tang dynasty is graphically illustrated by some booklets which have been stitched so that the thread passes through text nearest the spine of the book.

This proves that in particular cases, the stitching must have been applied after the book had been bound, and was not originally planned.

The thread bound books of the Ming dynasty developed out of the necessity to repair wrapped-back (baobei zhuang) books. The pages of this kind of book were held together with paper twists that were difficult to replace once they broke. However, we have seen that the practice of stitching a book for added durability can be traced back to the Tang dynasty. It is very likely that this practice endured, at least on a private level, up to the point when it ceased being merely a technique of book preservation and became the most popular form Chinese bookbinding in imperial China.

The Chinese pothi (fanjia zhuang)

Background

Until the adoption of Western binding techniques in China this century, the Chinese pothi was the only method of Chinese bookbinding that owed its existence to a foreign form of book - the Indian pothi.

This Indian format consisted of sheets of dried palm leaf cut into rectangular shaped pages stacked on top of each other. The pages were bound by string that passed through holes going through the middle of the document. All the pages would then be sandwiched between wooden boards that not only helped keep the pages together, but also protected the document from damage.

Left: The string passes through holes made in the palm leaf pages of a pothi.

Right: The pothi is protected by wooden boards and bound by the string that passes through the leaves.

The Chinese have two names for this type of book, both of which are descriptive: Fanjia zhuang literally means 'sandwiched Sanskrit binding', referring to the language used for Indian pothi and their usual storage method; and the other, beiye jing means 'palm leaf sutra', describing the material and the Buddhist nature of the texts. If we put the meanings of both of these names together, we get a very good description of this type of book: Buddhist sutras written in Sanskrit on palm leaves which are sandwiched together.

The spread of Buddhism brought this foreign format into China. After the fall of the Han dynasty in the third century AD, Buddhism started to take a foothold in China as many people saw in it a refuge from the strife and instability of the chaos that followed. As a result, many Buddhist texts found their way to China, including texts written on pothi. The religious nature of the Indian pothi had a great effect on the way in which the form would develop in China, but it also was eventually used for other kinds of book.

Characteristics

India and China had very different book forms before the invention of paper, and these forms were dictated by the materials involved. The smooth surface of the talipot leaf used for the Indian pothi provided a good surface for writing, and since the leaves were thin and flat they could be stacked on top of each other. However, these dried leaves were rather brittle, and therefore outer boards were necessary to stop the pages from breaking. Also, since the pages could not be bent or folded, it would have been out of the question to stitch the pages together at one side. Instead, a method was devised so that the pages could be turned without having to bend them; consequently the pages were strung together like beads, enabling the both sides of the leaf to be read without any danger of the pages losing their correct order. In China, however, materials like the talipot leaf were not widely available, and therefore would not have been considered as a possible writing medium. Wood and bamboo were widely available in China, and it is these materials that formed early Chinese books, antedating the Indian pothi. These materials, however, were not thin or flat, and could not possibly have been stacked like the pothi. Instead, the wood or bamboo was cut into thin strips that each generally held only one column of text. These strips were then bound together enabling the text to be read from one strip to the next.

The first form of bookbinding in China.

From this we can see that Indian and Chinese books developed in completely different directions as a result of the material available.

By the time the first Buddhist pothi books entered China in the third and fourth century AD, paper had already been in general use for two to three hundred years. It was to take at least another three hundred years for the Chinese to make their own pothi. The reason for this, too, possibly related to the fact that the materials were unsuitable for making this kind of book. Although Chinese books were no longer made of wood or bamboo, the fine paper produced in China was not much better for the purpose. In essence, Chinese paper was emulating the virtues of silk, aiming to be as soft and fine as possible (silk was used for book from the first millennium BC but it was expensive). Although paper was now thin and flat, its basic properties were still very different from palm leaves. If this early Chinese paper used the pothi binding system, not only would the pages be very difficult to turn, but the string that passed through the holes in the middle of the pages would also damage the paper and text. However, there is evidence to suggest that some sort of binding technique similar to the pothi was being used in the seventh century, at the beginning of the Tang dynasty (AD 618-907). It could not have been a common binding practice, since out of all the early Tang texts passed down to us, there is not a single extant book in this format. However, there are many Chinese examples of pothi in the Dunhuang collection, and although the examples kept at the British Library and the National Library of China are not dated, it is possible to tell that they probably all date from the ninth century onwards.

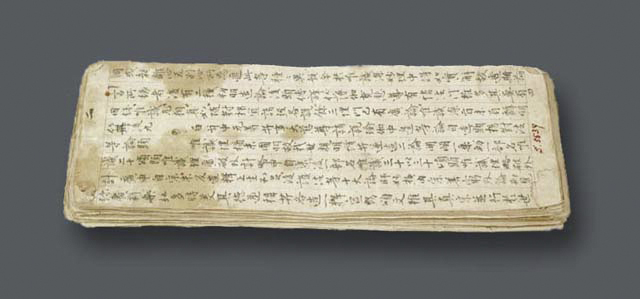

Many Chinese pothi had only one hole for string to pass through. Chinese pothi were wider than the original Indian versions.

The evidence that pointed to this period is again related to the physical material of the books, i.e. the quality of the paper.

Most of the paper of the Dunhuang books was not made in the Dunhuang region itself, but instead was made in central China and imported into Dunhuang. Situated at the edge of two great deserts, Dunhuang had a very dry climate, and as a result could not sustain the plant life needed for much paper production. However, from the eighth century onwards, as the Tang dynasty was in decline, the area surrounding Dunhuang was subject to much unrest, and as a result contact with central China suffered considerably. This meant that there was no longer an abundant supply of paper, and consequently paper had to be produced locally. Compared with the paper made in central China, local paper was thick and coarse, and it is therefore relatively easy for scholars today to recognise.

The extra thickness of this local paper made it more stiff and resilient to wear, and therefore made it much more suitable for making Chinese pothi than earlier paper. It makes sense, then, that the local people of Dunhuang started to make Chinese pothi only after the ninth century.

These paper equivalents of the Indian pothi seemed to be very similar in concept with the original: The pages, which are stacked on top of each other, are long, rectangular, and pierced through for string. Both sides of the paper are written on, and the text flows much in the same way from page to page as its Indian counterpart. However, among the numerous examples of Chinese pothi in the Dunhuang collections, almost none of them retain the outer protective boards or even the string. Yet we know that string had been used to keep the documents together since there is wear and tear of the paper around the holes. We also know that outer boards were used to encase the books, since an example still exists at the National Library of China . It is possible, therefore, that owing to the scarcity of wood in the region, the outer boards together with the string were removed to be used on new books when the old books were disposed of.

Left: Without either string or outer boards, pothi books are simply loose sheets of paper stacked in sequence. None of the Chinese pothi in the Dunhuang collection of the British Library have retained either string or wooden boards.

Or.8210/S.5537

Right: This is a Qing dynasty (AD 1644-1911) concertina book, complete with wooden covers. This is very possibly what the Dunhuang Chinese pothi would have looked like with their protective covers.

If, as some scholars hold, Cave 17 at Qianfodong in Dunhuang was used to store 'sacred waste' (i.e. books that are no longer needed, but are not destroyed owing to their religious content), it would be a possible explanation for the missing string and covers of these books.

Religion was at the heart of the Chinese pothi. They were brought into China by Buddhists, and spread throughout the country through the sheer popularity of the religion. When the Chinese started making this form of book, what interested them was more likely to be its connection with Buddhism rather than any additional convenience it offered in comparison with the scroll. However, this marked an important change in China regarding the relationship between text and binding, and also the way in which people regarded books. Previously in China, most books were written on scrolls, and there was no relationship between the text and the physical object. The arrival of the pothi in China meant that the text and the form of book were seen as separate things, and this must have had some effect on the development of other forms of bookbinding. The form of the pothi itself could have had an even bigger impact on the Chinese book owing to the way the pages came together.

Throughout Chinese history, books had always been rolled up for storage. The palm leaves of the Indian pothi, however, were stacked on top of each other, introducing the idea of the page. Therefore, it is even possible that the Chinese word for page (ye), which originally used the character for leaf (ye), came from the palm leaves of the Indian pothi.

Whirlwind binding (xuanfeng zhuang)

Background

Whirlwind binding is probably the most unusual of all the binding formats in the evolutionary process that ultimately replaced the scroll with thread bound book. Its unique structure reveals more about its place in the history of bookbinding than any other format, and the textual content of the examples found so far give us an indication as to why this evolutionary process took place. But although whirlwind binding was an established form of binding in its own right, it was purely transitory. It was a step in the development of book forms, and once more suitable forms were developed, whirlwind bound books were no longer needed.

By the Song dynasty (AD 960-1279), many other forms of bookbinding had evolved, and it is very possible that the production of whirlwind books stopped at about this time. This would explain why although there are many surviving examples of other binding formats, very few whirlwind documents have been discovered to date.

Owing to a lack of physical evidence, for a long time scholars were only able to speculate as to what whirlwind binding actually meant by using textual and historical sources. However, these sources were often very vague, and thus created misunderstandings which in turn meant that the few existing examples were overlooked until recent research brought them to light. This long search for the true identity of whirlwind binding has also made it one of the most fascinating book formats in Chinese history.

Old Chinese accounts of whirlwind binding are very rare. However, there was a trail of clues left by a Tang dynasty (AD 618-907) rhyme dictionary called Kanmiu buque qieyun (Corrected rhymes), by Wang Renxu. The Tang dynasty calligrapher Wu Cailuan made many copies of this text which apparently became very popular, and subsequently this text was often referred to as Wu Cailuan shu Tangyun (Wu Cailuan's Tang rhymes). From the earliest accounts from the Song dynasty up to the Qing dynasty (AD 1644-1911), references to whirlwind bound books have always been connected with this text. In 1980, Li Zhizhong discovered a copy of Kanmiu buque qieyun in the Gugong Museum, Beijing, and it is the discovery of this manuscript that brought the literary accounts and a physical object together for the first time. However, this manuscript had been rebound in the past, and although it is possible to have a good indication of how it was originally bound, it cannot strictly be regarded as a reliable example of whirlwind binding. Nonetheless, this important discovery facilitated the search for more concrete examples.

Several examples of what is believed to be whirlwind binding have now been discovered in the Dunhuang collections of the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the British Library. Most of these have not been rebound, so it is possible to get a clear impression how these manuscripts were bound and why they were bound in this manner.

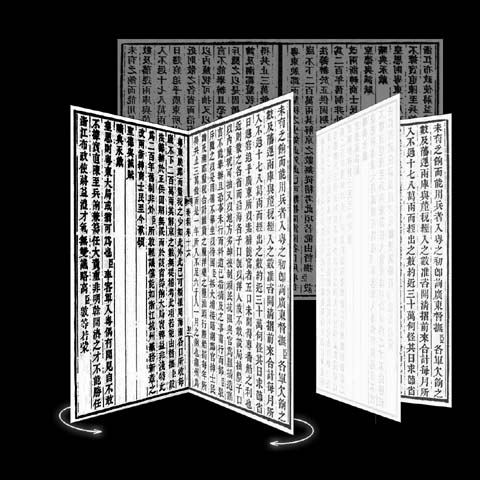

1) When a whirlwind book is rolled for storage it is indistinguishable from a scroll.

2) Whirlwind book rolled up for storage.

The roller at the centre of the document is the equivalent of the spine of a leafed book, holding all the pages in place.

3) The pages of a whirlwind bound book curl up when unfurled, suggestive of the circular movement of air in a whirlwind. This is very possibly how this book format got its name.

Or.8210/S.6349

Characteristics

Although it is still not known when the first whirlwind books were made, evidence suggests that it was probably during late Tang dynasty. The manuscript of Kanmiu buque qieyun in the Gugong Museum has a colophon that indicates it was copied and bound AD 749. During this period, the Tang dynasty was at its peak, the state was stable and affluent and culture flourished. Arguably the most potent expression of this culture was the writing of verse, which not only demonstrated an individual's cultural refinement, but was also a crucial skill for high government. During the Tang dynasty poetry composition reached an elegance rarely achieved in any other period of Chinese history. It is not surprising, therefore, that rhyming dictionaries were in much demand. Apart from rhyming dictionaries, many other reference books were also available. Therefore, it must have become apparent that scrolls were cumbersome to roll and unroll in order to consult specific portions of text, so a break was made from the conventional scroll format. Bearing this in mind, it seems more than a coincidence that all the whirlwind documents discovered to date are reference books of some kind.

It could not have been easy to break away from such a well-established method of binding books. Chinese bookbinding, binding techniques remained the same until the Tang dynasty, even though the materials used to make the books were very different. Before the widespread use of paper, documents used to be written on wooden or bamboo strips that were bound by being tied together with string. The strips would be tied together in parallel, so that when the document lay flat, the vertical lines of text would lie next to each other and thus the document could be read.

For storage, the bound strips would be rolled up. This was the first form of bookbinding in China, and this concept of binding as well as storage lasted for over a thousand years.

The paper scroll was simply a development on the same principals. Individual sheets would be pasted one after the other with no break in the text, so that the document appeared to be on one continuous sheet of paper. It was also rolled up for storage. However, the sheets of paper of whirlwind documents were put together in a completely new way. Instead of being pasted in sequence like a chain, the individual sheets were stacked on top of each other, forming individual pages or leaves that could be turned like a modern book, making it much easier to consult a long text.

It is very difficult to know for sure what inspired this break from the accepted form of binding, and it is perhaps difficult to accept that there was no other influence at work. However, there was already another form of book in China that had been around since the fourth century AD: the pothi . Although evidence so far indicates that the Chinese did not write texts on pothi or develop their own form of pothi until the Tang dynasty, the existence of these books in China meant that by the time whirlwind documents were being made the concept of stacking pages had already been in China for centuries. It is difficult to imagine that the pothi format had no role in influencing the idea of stacking the sheets of text in whirlwind binding.

Although it is arguable whether or how much the pothi format influenced the development of whirlwind binding, the subject matter contained within these books remained different. Pothi were all Buddhist texts, and whirlwind books were reference in nature. Therefore, it appears that at this early stage of the Chinese departure from the scroll, the subject matter of the text had an influence on the evolution of different formats. This was an important development in the history of Chinese bookbinding, marking a substantial change in the way people thought about books. The specific functionality of a book was considered as well as the contents of the text.

Even though whirlwind binding was an improvement on the scroll format, its greatest strength was also its weakness, it served as a bridge between the past and future forms of Chinese books. This is not to say that all subsequent binding methods developed from whirlwind books, it is simply an observation of its form and function: It has pages that are bound like a modern booklet, but it is rolled up and stored like a scroll. The scroll format had been around for so long that it was impossible to change the concept altogether.

Description

This is a description of the only known example of whirlwind binding in the Stein collection of the British Library.

Library no.: Or.8210/S.6349

Title: Wuzhai xiongji fa (Divination of fortune and calamity).

Size: Five leaves in total, all approximately 30cm high.

Width: page 1, 22.5cm; page 2, 30cm; page 3, 30cm; page 4, 50cm; page 5, 68cm.

Binding method:

Successive pages were stacked on top of each other so that the shortest page was at the top and the longest page at the bottom. Then the pages were aligned down the left hand side and pasted together at the edge. A bamboo rod which had been split in half was used to sandwich the pages together at the left hand edge, and holes were pierced through the bamboo rod and the paper for the document to be strung together.

Each sheet of paper is longer than the previous sheet.

Complete whirlwind bound book unfurled.

To store the document,it would be rolled up like a scroll, whereby the bottom page - which is longer than all the other pages wraps around the outside of the document, forming a kind of wrapper, so that externally it is indistinguishable from a standard scroll.

The method in which this manuscript was bound is consistent with other examples discovered so far, indicating that whirlwind binding was indeed a standard form of bookbinding in its time.

Concertina binding (jingzhe zhuang)

One of the most interesting features of concertina binding is that it appears to be a synthesis of the traditional book forms of both China and India. Moreover, it was the first type of Chinese binding that took the external form of a booklet, making it another important format in the history of Chinese bookbinding. Despite this, not very much is certain concerning the history of its development.

As in the case of the Chinese pothi (fanjia zhuang), Buddhism was at the heart of the concertina format, and for this reason it was named jingzhe zhuang (folded sutra binding). By the late Tang dynasty, the concertina format was being widely used by Buddhists around China. This suggests that its development dates back some time earlier, possibly around the time when Chinese Buddhists started using the Chinese pothi format. Chinese pothi books, however, never became popular. This was mainly owing to the relationship between its physical form and the materials used to make it (see article). The use of the concertina book, on the other hand, became very popular indeed, and yet both of these book forms were used almost exclusively by Buddhists. Therefore, if we regard these two book forms as two similar styles competing for survival in an evolutionary chain, it is possible to consider some of the possibilities concerning the transformation from the scroll to the double leaf book.

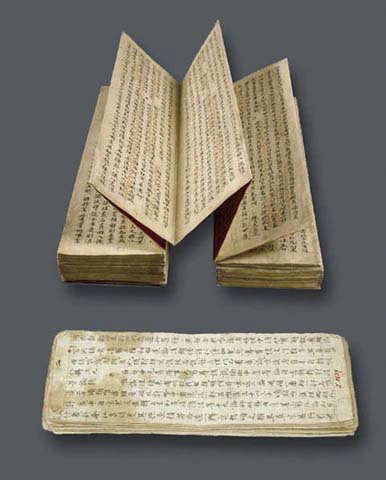

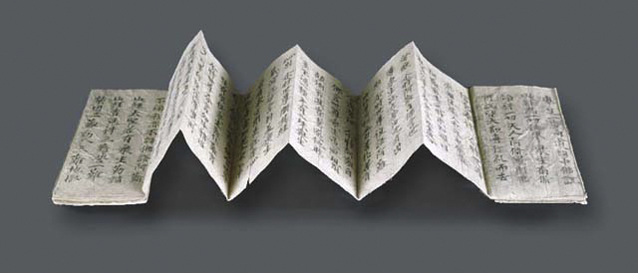

The earliest known extant concertina books, like many other Chinese book forms, were discovered among the Dunhuang collection. Judging from the shape of these examples, it appears that there was a conscious desire to imitate the Chinese pothi form. The folios of this new book were long and thin, on which the text was written vertically so that each column would hold many characters, but each folio could only have a few columns each.

There are many similarities between the concertina and the Chinese pothi formats. The concertina book (top) has had holes pierced through the pages in the style of the Indian pothi. These holes cannot perform any practical function since the folios are pasted together and the book cannot be read like a pothi. However, it does display the influence pothi had on the concertina book, especially the strong relationship between content and form.

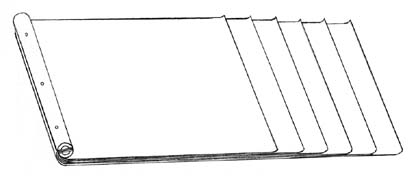

Modern concertina book, spread open revealing the concertina-like folded paper.

It is possible to see from this angle that if the concertina book was not folded it would essentially be a scroll.

Or.8210/S.5603

Dimensions (cm): 8.7 x 28.3 per fold

In this respect, the concertina was almost identical with the Chinese pothi. However, unlike Chinese pothi, the concertina probably evolved from the Chinese scroll. This transformation was made by simply folding the unfurled scroll back and forth like the pleats of a concertina, thereby forming separate folios, and enabling the reader to flick through the text.

This meant that not only did the form resemble the Indian pothi, but it was easier to turn through the text as well. Moreover, since there was no string passing through the middle of the document, much less damage was caused to the paper and so the book would last longer. Using this method, existing Chinese scrolls could simply be converted into concertina books. Although it is not certain to what extent this was practised, there are extant concertinas that were formerly scrolls in the Stein collection of the British Library.

The quality of this very small concertina sutra indicates that it was very possibly used by the same person who made it. Its small size and shape made it easy to carry.

Or.8210/S.5618

Dimensions (cm): 6 x 13.5.

This concertina booklet has been cut and folded in a coarse manner. Convenience, not appearance, was the most important motive for making booklets in Dunhuang.

Or.8210/S.5618

This item is a mixture of the concertina and butterfly formats. It is also the only printed booklet in the collection. Originally folded in the concertina style, the folded edges of the book were pasted together like the folded leaves of the butterfly format. This simple modification to the concertina format would have made the book easier to carry and to turn the pages.

Or.8210/P.11

Dimensions (cm): 10 x 14 per fold

By using this simple comparison of the two formats, it is easy to see why the concertina format superseded the Chinese pothi in the evolutionary chain of Chinese bookbinding, and then went on to influence the development of other styles.

The biggest innovation the Indian pothi introduced into China was the stacking of leaves to form separate pages. This made the book easier to recite, and also easier to carry. These two aspects of the format obviously played a large part in the development of the booklet in China. This is especially prominent in the Dunhuang area where there were many practising Buddhists. Most of the booklets recovered from the Dunhuang cave library were Buddhist sutras that were almost certainly personal copies made to be carried on the person (see example). Consequently, it was natural for the concertina to become a popular format.

Although the concertina book undoubtedly contributed toward the development of other styles, it is very difficult to say how that development took place, and just how strong the influence was. There are some booklets in the Stein collection of the British Library that appear to be a cross between the concertina and other forms of binding.

While these examples cannot be taken to represent historic evidence of a specific development, they are still very interesting to see in order to imagine how a particular evolutionary step might have taken place.

Wrapped-back binding (baobei zhuang)

Wrapped-back binding became widely used in the Southern Song dynasty (AD 1127-1279) and completely replaced the butterfly format by the Ming (AD 1368-1644). The biggest difference from butterfly binding was the design of the folded leaf. The folded leaf, in turn, had a strong relationship with the printing block which probably led to the development of this format.

The major flaw in the design of butterfly binding was that, owing to the way each leaf of the book was folded, every second page of a printed book would be blank.

Wrapped-back books solved this problem by simply folding the pages the opposite way round. Each sheet of paper was still only printed on one side but, after being folded, the wood block print would appear on the 'outside' rather than the 'inside' of the folio.

This shows a folded leaf printed with one wood block (in the background) to form a double page. The arrows indicate the direction of the fold in butterfly binding. Each folded page is only printed on one side, the other side remains blank. Therefore, when these pages are pasted together, every two printed pages are followed by two blank ones.

The wrapped-back and butterfly leaves are folded in opposite directions. In both formats, the other side of the leaf remains blank. Therefore in the wrapped-back fold, the blank sides are folded in on each other and are never seen.

These folios were then piled up on top of each other so that the open ends, instead of the edges, of each folio came together to form the spine of the book.

This meant that the blank side of each folio was folded into itself and bound so that it could no longer be seen. Instead of being pasted together like butterfly books, the folios were bound together using paper twists that passed through the spine of the book. A cover was then attached to the book, protecting the spine and outer pages. Wrapped-back binding evidently acquired its name through this particular feature of its design.

There are no examples in the Dunhuang collection of books with all these features. However, there are some booklets that have had outer covers pasted around the back of the book for extra protection and reinforcement.

It is difficult to determine whether this feature alone qualifies these booklets to be categorised as early examples of wrapped-back books. Nevertheless, these booklets are very interesting to examine in order to imagine the circumstances under which subsequent binding techniques could have evolved.

The pages of this modern thread bound book are folded in the same way as the pages of wrapped-back books. The open ends of the folded pages come together to form the spine of the book. The folded edges are at the 'mouth' of the book.

This butterfly bound book has had a layer of paper pasted to the back for reinforcement. The pasted folios have become detached near the centre of the book, but the paper cover is keeping the book from breaking apart. This manuscript demonstrates the weakness of butterfly binding and the necessity of adding reinforcement.

Or.8210/S.5432